A practical way forward in the new Renewable Portfolio Standard

Moderate targets, small but meaningful penalties, and a 2030 goal that can be met by wind alone with no new transmission.

On Monday, a proposal for a Renewable Portfolio Standard was filed in the Alaska House. Luckily, I am the proud owner of a ridiculously sprawling set of spreadsheets full of Railbelt electricity data, which I quickly pulled out to answer what I see as the some of the most important questions about this bill:

What does it do? Can we meet the goals? What happens if we don’t meet the goals? What will this save or cost customers?

It requires the Railbelt to reach 40% renewable energy in 2030, and 55% in 2035, with fines for non compliance. The 2030 goal could be met by already-proposed projects without new transmission. The worst case scenario, where no one even attempts to comply and no new projects are built, could raise bills by 5.5% in 2030, and 8.5% in 2035. If utilities do comply, costs might be about the same, or bills could be lowered by as much as 10%, depending on currently unknowable economic details. Renewable energy projects have their big costs up front, so these new projects will provide some price stability and a hedge against volatile future fuel prices.

Enacting the RPS requirements could attract competition to our tiny energy market, providing pressure on both renewable energy and gas prices. Implementing them would also be a substantial step toward addressing the natural gas crisis.

Over the next 10 years, HB 153 would bring the Railbelt from 15% renewable to around half renewable.

Currently, the Railbelt gets around 15% of its energy from renewable sources. This bill requires the Railbelt to get 40% of it’s energy from renewable sources by the end of 2030, rising to 55% by the end of 2035. While the last RPS bill set both a long term ambitious goal (80% by 2040), and a short-term smaller goal (25% by 2027), this bill chops off both those ends, focusing on medium-sized goals over a 5-10 year time frame.

Renewable energy is defined in a generally conventional way, including hydro, solar, wind, geothermal, tidal, and biomass. This is in contrast to a previous Clean Energy Standard that attempted to define all our coal plants as clean.

The energy generally has to be physically produced on the Railbelt, but utilities are also allowed to meet the requirements with credits bought from rural Alaska communities eligible for Power Cost Equalization (PCE). There are extra incentives for large wind projects that provide energy to multiple utilities, and for distributed generation (such as rooftop solar). These incentives take the form of multipliers, where the energy produced is counted as more than it actually is for the purpose of meeting the standard. Distributed generation gets a 2x multiplier, while large shared wind projects get a 1.25x multiplier. The biggest in-the-pipeline renewable projects on the Railbelt are wind projects that would qualify for this multiplier.

The 2030 goal could be met by already-proposed projects. And we’d only be 2% short of the 2035 goal

While there are many possible ways to meet the standard, I’ve analyzed a set of in-the-pipeline projects with publicly available production numbers and timelines, where utilities have already modeled integrating the power into their systems.

By far the largest chunk here is Alaska Renewables’ two wind projects at Shovel Creek and Little Mount Susitna. They are still pursuing both projects, and say that their projects do not depend on the continuation of federal tax credits. Importantly, they also don’t require any new transmission, according to an extensive integration study commissioned by the Railbelt utilities. The Railbelt has often been described as a “long extension cord,” and while new transmission would have benefits, there is a lot that can be built before that happens. This scenario would require the utilities to work together using “economic dispatch,” which means they’d run the cheapest power plants first, regardless of where they are and who owns them. This pair of projects, on their own, more than meet the 2030 goal.

The other projects I’ve included here are the state’s Dixon Diversion project (which would add more water to the Bradley Lake hydro facility), and a project modeled on the Puppy Dog Lake solar project. Though the Puppy Dog Lake contract was recently canceled, it’s possible that that project could go forward in a different fashion. Even if not, the production numbers in the contract are a reasonable estimate of what a similar solar project might produce, and HEA already modeled its integration into their system. Since both of these are on the southern end of the Railbelt, where transmission is more constrained (the bottleneck is South to North), it’s possible that adding these to the wind would require additional transmission. But they aren’t required to meet the 2030 goal.

I also modeled that all existing renewable projects continue to produce at recent average levels, and that distributed solar increases at a recent average rate. Potential renewable energy credits purchased from PCE-eligible communities aren’t included in the graph, but could cover around 1-2% of Railbelt energy. For simplicity, I’ve assumed flat electricity loads into the future. This matches recent history, but of course, the future might be different. If loads rise, more renewable energy will be required to hit the goals, but the increased loads will drive rates down (through spreading out the non-fuel fixed costs of the system).

In the worst case, the Renewable Portfolio Standard could raise costs 5.5-8.5%

Let’s do the worst case first. This is really a straw man, but is useful to get a sense of scale. Potential costs to ratepayers are driven by the fines the bill imposes for non-compliance. So to get the worst-case scenario, we need to assume that all possible renewable energy projects are more expensive than the cost of existing energy plus the proposed fines, and therefore absolutely no new renewable projects are built in the next ten years. We also need to assume that the utilities are pretty much ignoring the law, and that none of them manage to get any fines waived for “good faith efforts” to comply, factors outside of their control, or signing contracts for facilities that aren’t built yet.

When I wrote about the last Renewable Portfolio Standard proposal, I said that the fines that would be imposed on the utilities for not complying were so small as to be meaningless. That is no longer true in this version. First, the fines have been raised from $20 per megawatt hour to $45. More importantly, they’ve been adjusted for inflation (any dollar number in a piece of legislation should be adjusted for inflation!).

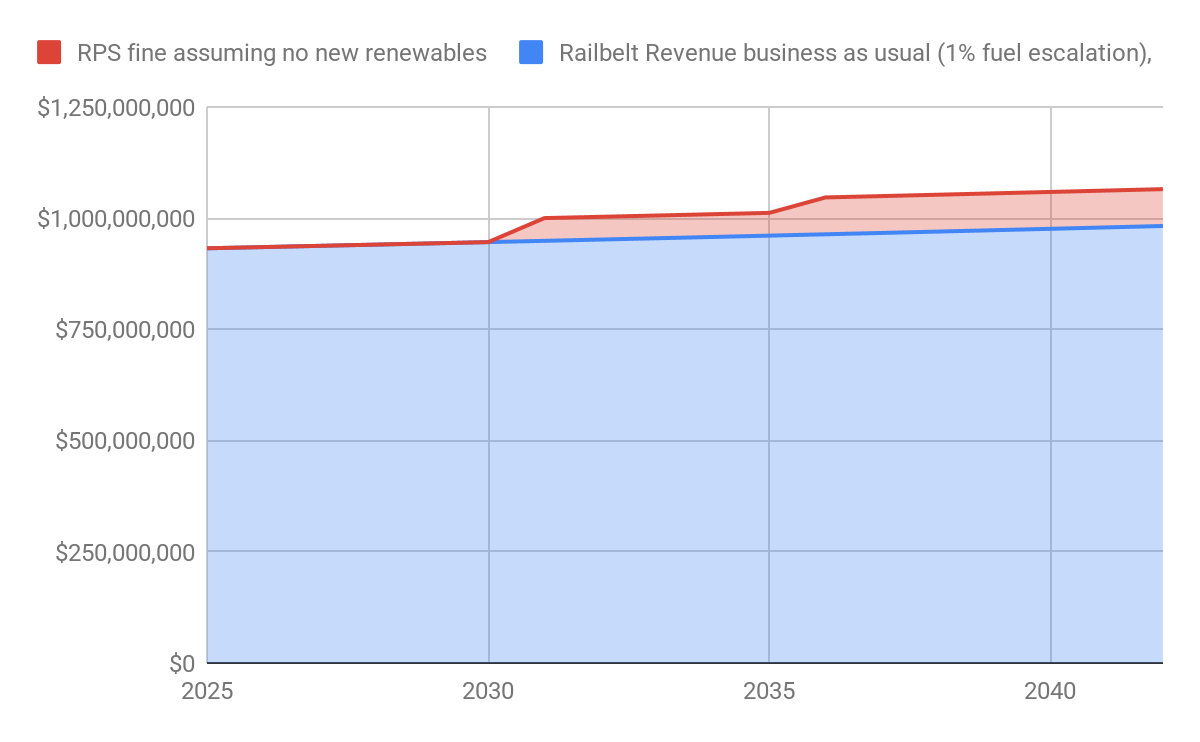

I assume here that non-fuel costs rise exactly with inflation, and fuel costs rise 1% faster than inflation. Gas costs will likely rise more, making the percentage impact of any fine smaller.

In this “do nothing” scenario, fines would kick in at around $50 million total across the Railbelt in 2031. That represents around 5.5% of total Railbelt revenue. So, it could raise bills about that amount over what they would otherwise have been. If everyone continued to do nothing for the following five years, that would reach 8.5%. This is meaningful, but not earth-shattering.

In my opinion, meaningful but not earth-shattering is probably a good place to be for fines that are intended to drive action. Without meaningful incentives, nothing tends to happen. This can easily be seen in the 50% renewable target the state was supposed to meet this year (set by the Palin administration), as well as voluntary goals set and missed by individual Railbelt utilities. On the other hand, while customers are responsible for their utilities’ decisions (these are all democratically-run cooperatives), it’s nice if individual customers aren’t entirely screwed over if their utilities make poor choices. It’s a balance.

A more reasonable bad case might be kind of a wash

It seems quite unlikely that all the Railbelt utilities would neither build/purchase any renewable energy nor get any waivers. But what if they do, and renewables are expensive? A lot of factors impact renewable energy prices, including interest rates and federal tax credits. Tax credits, as they exist today, could provide a 40% tax break to these projects. But that might be zero tomorrow. Our existing energy also has super uncertain costs, as we move to imported gas from one or two unbuilt import facilities, with unknown costs, and a supply price driven by global markets.

From that impossible mess, I’ll try and pull what numbers I can. The economics of Railbelt power plants are public data, so it’s easy to substitute higher gas prices into existing generation cost data.

Current gas generation costs are around 7.8 cents per kilowatt hour (total cost of power as it leaves the power plant, for all gas plants on the Railbelt in 2023). This will rise as gas from old Hilcorp contracts and Chugach Electric’s gas field is replaced by newer more expensive contracts and expensive imports.

Future gas generation costs might range from 11 cents per kilowatt hour (most efficient gas plant with Furie’s $12.30/Mcf gas) to 16 cents per kilowatt hour (less efficient plant with $16 gas). Oil generation costs and Healy 2 coal generation costs are already in that range or higher.

The wind integration study I referenced earlier says that the 300 megawatts of wind would pencil out (saving consumers money) if it cost between $97 and $126 million each year in total, equivalent 8.2 to 10.3 cents per kilowatt hour. [edit — I had higher numbers here earlier (9.7-12.6), as I accidentally wrote total costs in place of costs/MWh] Since the developer says they aren’t relying on tax credits, presumably they can hit this range without them.

The developer of the canceled Puppy Dog Lake solar contract mentioned tax credit uncertainty in their news articles. Their contract price was 7.4 cents per kilowatt hour. Taking away an assumed 40% tax credit would give you a price of 12.3 cents.

So one plausible scenario is that we meet the goals and all the new energy, gas or renewable, costs around 12 or 13 cents per kilowatt hour (wholesale).

In a good case, the Renewable Portfolio Standard could lower costs around 10%

If you assume that tax credits continue, reaching the RPS goals could save a significant amount of money.

Last time there was a Renewable Portfolio Standard bill for the Railbelt, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory did a study on the potential economics. Their assumptions included renewable energy tax credits, and imported gas costs. While the study looked at a higher renewable target (80% by 2040), the earlier years in that study look a lot like this current RPS.

The targets from this current RPS bill line up pretty well with the generation mix around 2029-2030 in the least cost scenario from that study. Cost savings over a no new renewables scenario were around $90-$100 million in that time frame, which would be about 9-10% of total Railbelt Revenue.

There are non-price benefits to adding more renewables

Other than straight up energy price impacts, what would this do? On the minus side, integrating variable renewable energy is more complicated than turning on a gas plant. There’s no re-inventing the wheel needed, since this has been done all over the world (including in some rural Alaskan villages), but it takes careful modeling. On the plus side, renewable energy projects will provide price stability and a hedge against volatile future fuel prices. Also on the plus side, any renewable energy we add to the grid saves Cook Inlet gas. This is important, because while there are now two preliminary plans for import facilities, nothing is a done deal yet, and shortfalls are still quite possible. Even without actual shortfalls, any gas saved will displace imports. Renewable energy also has vastly lower carbon dioxide emissions and emissions of other pollutants, which is important for mitigating climate change, and for human and environmental health.

If this is a good idea, why would we need to legislate it?

In a perfect world, you might imagine that all utilities always make the best decisions for their members on their own, and no legislation or regulation is ever beneficial. But, well, the world is imperfect. Doing things is always harder than kicking the can down the road, even when those things are beneficial or necessary. The Cook Inlet gas situation is a great example of this. Fuel prices are an especially easy place to kick the can down the road, since these enter our power bills in automatically-calculated ‘cost of power adjustments’ that don’t require anyone to actually vote to raise rates.

Mandatory goals can push us into action, add certainty, and lower prices through competition.

Certainty makes things easier. To reach these goals, utilities likely need to negotiate complicated contracts with each other, and with independent power producers. On the Railbelt, we have four major utilities with four different management teams and four different boards of directors, adding up to dozens of individual humans with different goals and viewpoints and relationships. If they have to be on the same page, that simplifies negotiations.

The standard itself will likely lower costs by increasing competition. Right now, we have just a couple of local companies that can build major energy projects. So when the only solar company has to cancel its plans, there’s no one else to turn to. A standard could attract more renewable energy companies to compete with each other, knowing that there’s a guaranteed demand. And because renewable electricity also competes with gas electricity, it can provide pressure on local gas prices as well.