Energy conservation is good. And raises electric rates. What does that mean for net metering reforms?

Anything that affects use affects rates, but the impact of net metering expansion would be insignificant. Rates can't be both fair and aligned with costs, but we should still work to save fuel.

Solar panels on roofs. Everyone seems to want to talk about them, lots of people have questions about them, and the flow of energy and money is genuinely complicated. As I find myself in more of these conversations, I realized I needed to try to answer the thorniest and most controversial question for myself. When some people put up solar panels, is it good or bad for the system as a whole? Is it fair?

On the Railbelt, solar panels on houses and businesses produce a tiny fraction of our power today (0.3%), but still more than utility-scale solar (0.25%). That number has grown rapidly in recent years, and a number of policy and regulatory changes are poised to expand or contract it. A community solar bill was signed into law this summer, but its rate structure hasn’t been defined yet. Rules that would make home solar more favorable (annual net metering), or less favorable (net billing), have cropped up in past legislation, and are likely to do so again. Rules in other states have been changing. The Regulatory Commission of Alaska has recently proposed rules that would raise the “cap” on Railbelt net metering to 20% of demand (about 2% of energy generated).

If we get more of these ‘distributed energy’ systems, what happens?

At the numbers we’re talking about (possibly reaching up to 3.7% of energy sales with net metering maxed out, and 100MW of community solar), the physical impacts of that solar energy on the system are pretty small. Mostly what would happen is that we’d burn less fuel, and people would buy less power.

Buying less power is the heart of the controversy. Your electric bills depend, in part, on everything your neighbors do. Installing solar panels, insulation, or a hot tub. Buying an electric car, or becoming a snowbird. If your neighbors conserve power, and you don’t -- your bills will go up. In most of the country, individual households buy significantly less power than they used to. In a few states, distributed solar systems are a significant reason for that, but not in Alaska. It’s probably not a surprise that Alaska is firmly in the bottom half of the nation for distributed solar.

But conservation has played a huge role here. Since 2010, Railbelt per household electric use has dropped 15%. Individual consumers have saved over 50 billion cubic feet of Cook Inlet gas through electricity conservation, and utilities have saved over 50 billion cubic feet through power plant upgrades and pooling. This is despite the addition of more than twenty thousand new electric customers. All those savings add up to around four years of electric utility gas use. Without them, we’d likely be importing gas already.

Here are a few facts about household Railbelt electric bills that might surprise you.

Alaskans use less electricity per household than all but four other states.

Our bills are lower than the US average -- $1555 per year vs. $1623 per year.

They are the same now as they were in 2010 (after adjusting for inflation).

One could take this as a reason to focus less on electric rates and more on heat bills, but somehow we don’t, and people can’t stop talking about electric rates. So here you go.

Distributed solar rate impacts would be tiny

If we want to know how more distributed solar might impact other people’s energy bills, we can do two things. 1. Look back at what did happen when we saw a much larger drop in electric use, and 2. Look forward to what could happen if we add solar systems and keep everything else the same. Luckily we can do this, because all the Railbelt utilities are cooperatives. We have public data on fuel costs, other costs, electric use, and money collected from customers, and can model what might happen if any of these things were different.

By conserving power, consumers have kept average annual bills pretty constant. However, if you didn’t get in on those efficiency improvements, and still use the same amount of power as you did in 2010, your annual costs are $275 higher. How does this compare to the potential impacts of distributed solar? If we assume rooftop solar systems grow to fill the RCA’s proposed cap, average bills go up around 60 cents per month. Community solar doesn’t have a rate structure to model, so for a placeholder, let’s say it works like adding 100MW more rooftop solar, roughly doubling the proposed cap. Together, that would add up to a $1.40 increase on a monthly bill, or around $17 per year.

Everything else will change bills a lot more

Everything else that will happen in the time it might take to reach that level of distributed solar will have much larger impacts. All the distributed solar I modeled could raise electric rates around half a percent, spread over however many years it would take for it to be installed. Over the past year, Railbelt electric rates have changed an average 3.5% every quarter, sometimes rising as much as 23%, or dropping more than 9%. This is mostly due to shifts in fuel and purchased power costs. The Cook Inlet gas crisis will drive this further, possibly raising rates around 10 to 17% depending on the costs of outside gas.

Fuel savings benefits outweigh costs to other members

If distributed solar doesn’t make much difference to rates, does it matter for fuel savings? On a percentage basis, if you add 3% solar energy, you’ll save roughly 3% of the fuel. Added up, that’s around 950,000 Mcf of gas (from the gas dependent utilities: CEA, MEA, and HEA), and 3.3 million gallons of oil (from GVEA) per year, similar to the potential fuel savings from the Dixon Diversion project. It doesn’t solve climate change or the gas crisis, but it’s a significant piece.

It’s especially relevant because it’s additive to all the other pieces, and can happen more quickly. It doesn’t require either utilities or the state to spend money, negotiate contracts, or build anything, and therefore it can happen beside all those larger efforts.

Utilities should focus on bigger things

Utilities are likely to provide much of the testimony on any regulations or bills involving distributed energy. This is silly. On an individual consumer scale, installing distributed solar has large financial and environmental impacts. On a utility scale, it doesn’t.

Utilities on the Railbelt are all cooperatives, and work for their members. Allowing interested members to connect solar systems reduces fuel use and emissions a modest amount and empowers those members to lower their bills. But utilities can do vastly more to reduce fuel use and costs for all their members with utility-scale renewable projects.

HEA just signed a contract to buy power from a 30MW solar farm that will more than double all the solar on the Railbelt in a single shot. The other Railbelt utilities are in negotiations with wind power developers for much larger projects. Utilities have yet to nail down where their natural gas is going to come from. These are the sorts of decisions that make a difference for the members as a whole.

Is it fair?

A big argument against net metering is that while the environmental benefits of burning less fuel are enjoyed by the entire world (climate changing emissions), and entire community (local air pollution), rich people receive all the economic benefits. High-income people are more able to afford solar panels. The small size of the rate impact renders that irrelevant here, but additionally, half of the distributed solar I modeled is community solar (which should be accessible to low income people) and the state also has a grant to help low-income households install solar.

But for some people, it’s the principle that matters. The fact that one person’s actions affect another person’s electric rates seems fundamentally unfair. This argument has three major problems:

If raising your neighbors' rates with your solar panels is unfair, so is raising them by buying a better refrigerator, or lowering them by buying an electric car.

Rewriting rates in such a way that your power use doesn’t affect your neighbors rates would mean raising costs dramatically for anyone that doesn’t use much electricity -- which would cause vastly more harm to low income people than more solar panels ever could.

Electric rates are designed to charge consumers based on their responsibility for past infrastructure decisions, not current marginal costs.

You might think you can calculate how much it costs the utility to serve a house with a solar system on it, see whether those houses are paying more or less than that number, and adjust accordingly. It turns out you can’t possibly do that. And to explain, I have to back up and explain electricity rates more generally.

Fair electric rates are a fiction

An electric utility has a bunch of costs, and a bunch of customers to divide them between. Sometimes it’s easy. Add up the cost of fuel, divide it by the number of kilowatt hours produced and charge each person that much per kilowatt hour. That becomes part of the “Cost of Power Adjustment” on an electric bill. Everything else is much less straightforward.

What is each customer’s fair share of power plant debt, lineman salaries, new transformers or regulatory compliance?

There are standard ways this is usually done, based on a cost allocation manual from 1992, that involves dividing customers and costs into categories, then deciding how much responsibility each category of customers bears for each category of costs.

Those standards, baked into RCA regulations, don’t fit how our actual costs work. For instance, a large portion of total costs, including most of the costs of the power plants themselves, gets classified as “demand.” Which means that we look at the hours of the year when people used the most electricity (cold days in winter), figure out who used the most at those times (houses), and then assign them a higher portion of power plant costs. This is based on the theory that the power plant got built because the old power plants couldn’t provide enough energy to meet the highest demand.

But that’s not true. The natural gas plants that provide the majority of the power on the Railbelt today were built to be more efficient than the old ones because gas prices were going up, even though demand was going down, and there was no problem delivering enough electricity. But the fact that residential customers used more power in some of the coldest hours a decade ago is part of the reason for their rates today.

That doesn’t seem fair. It seems even less fair for a snowbird or a fish processing plant that never used power in the winter in the first place. Even when the division of costs isn’t obviously wrong, it’s still contentious (this RCA order is 89 pages long, and only summarizes all the division arguments in the Chugach rate case). And even the categories themselves are pretty arbitrary. Why should a house pay a different rate than a coffee shop, while an apartment in a dense city core pays the same rate as a house at the end of a long rural road lined with beetle-killed spruce trees?

The principle is that the “cost causer should be the cost payer.” Which means “we divide things into broad and fuzzy categories based on a decades old manual in order to figure out whose fault it was that the utility had to buy that thing in the first place” not “we charge you based on how much it costs to bring electricity to your house.”

The logic of per-unit rates collides with the day-to-day reality of fixed costs

Almost everything in your electric bill changes based on the amount of electricity you use. On the other hand, most of an electric utility’s budget stays the same.

From the “cost causer should be the cost payer” principle, dividing costs by the amount of power used makes a lot of sense. It’s supposed be divided based on the reason things were built, and things get built based on the amount of power they need to deliver. If my house used as much as a refinery, we’d have built a bigger power plant and bigger transmission lines. If the refinery used as much as my house, we’d have built everything smaller.

But on a day-to-day basis, most of these costs don’t change if people change their power use. Fuel costs do, but the infrastructure is already built, the people are already hired, and the debt is already incurred.

Another way to think about it is that everyone should pay the same amount for those fixed costs. No one advocates for that on an absolute level (that a house should pay the same fixed costs as a hospital), but some people do within a category (all houses should pay the same fixed costs). But this is just as arbitrary and no more fair than the way we do it now.

To explain, let’s take the example of my property. My utility is HEA. In 2023, the average HEA residential customer paid just over $1700. $500 of that paid for fuel and Bradley lake hydropower. The other $1200 went towards fixed costs.

My house used a little less power than average, so I paid $1100 in fixed costs. My sister in law has a house on the same property that also used a little less power than average. She paid $950 in fixed costs. If you take that $1200 number as the correct one, we’re both being subsidized -- to the tune of $350 total per year. What if I connected her house to my meter? Suddenly we’d turn into a single customer paying $1750 for fixed costs. It would appear that my family was overpaying -- subsidizing all the other customers $550 per year. But we’d actually be paying $300 less in electric bills. The actual costs to HEA of serving my property would be the same.

Confused yet?

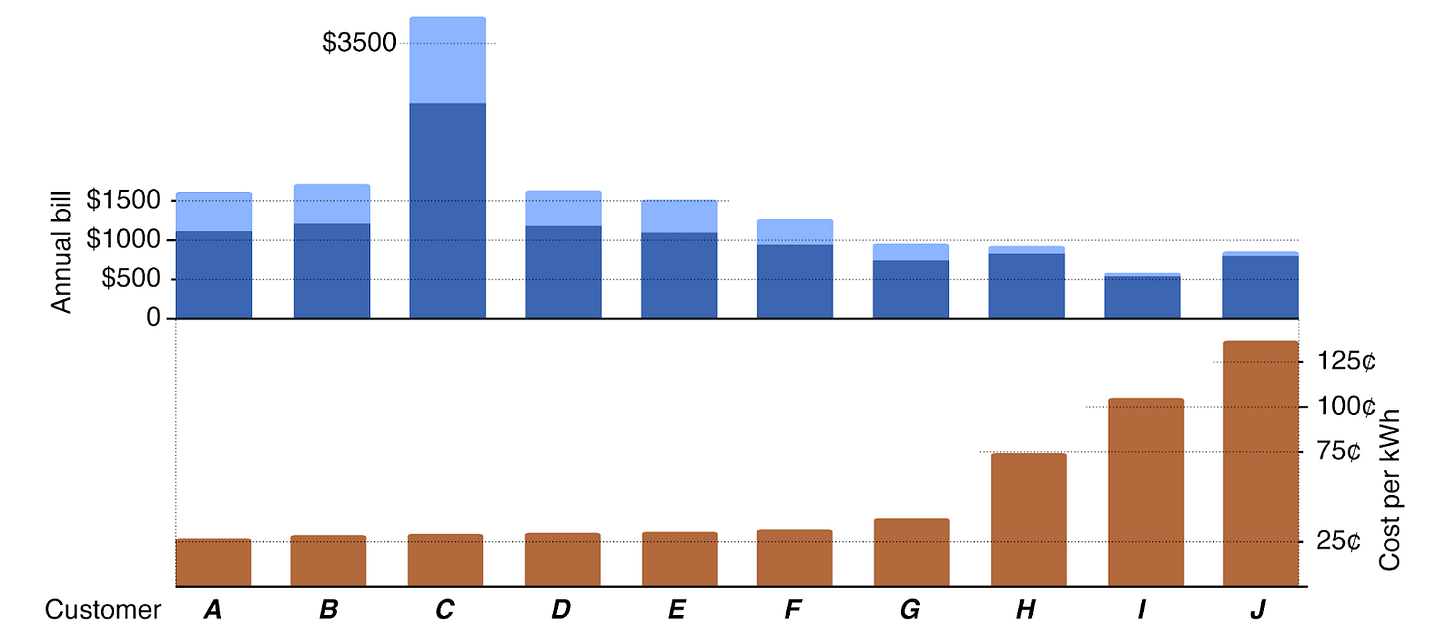

Here’s some more example HEA customers, with graphs showing how much they paid over a year in fixed costs, power costs, and per kilowatt hour.

Dark blue bars are fixed costs, light blue are fuel and purchased power cost.

Customer I paid the least fixed costs - only $550. Under the “$1200 is correct” framework, they’re being heavily subsidized. On the other hand, with HEA’s mandatory minimum payments, they’re paying over $1 per kilowatt hour for their power, much more than in a lot of rural villages. If every customer were a customer I, we’d have built a very different power system in the first place. Customer I is paying a lot for the debt and depreciation for our new natural gas plants, but isn’t benefiting from it much.

If customer I had to pay $1200 in fixed costs, they would pay $2.23 per kilowatt hour. With such a small use, and such a high price, they’d probably disconnect entirely -- and the utility would collect less money overall. Customer I could, in fact, argue that almost any amount they pay for fixed costs is actually a benefit to the utility, since the utility would otherwise get nothing from them. Maybe they could offer HEA $100 per year instead. That doesn’t sound fair, and we don’t allow it for houses, but this is exactly how rates work for large industrial customers.

The Marathon refinery gets its power from a special contract, for around 2 cents per kilowatt hour beyond the generation cost. The rationale, as written in the contract, is that since the refinery would otherwise generate its own power, as long as it pays HEA a little more than the cost of that power, it’s a benefit to everyone else.

The people contributing the least to fixed costs often aren’t the ones with solar panels.

Who are customers A-J? Most are real houses on the HEA system that shared their bills with me. Some have solar panels, some have heat pumps, some have both or neither. Two are 2023 averages from RCA filings -- the average of residential customers with and without solar panels. One is a theoretical customer with average use and a 6 kilowatt solar system, which I used for my rate impact analyses at the beginning.

The person paying the most towards fixed costs actually has a very large solar system. The people paying the least don’t have solar panels at all. Small houses and apartments (often occupied by lower income people) often don’t use much power. And people that use more power are disproportionately likely to buy solar systems. Which is probably why the average house and average net metering house are so similar.

It’s all about the fuel

What about duck curves? Peaker plants? If you read about net metering regulation debates in other places, there are all sorts of factors I haven’t mentioned at all. That’s because they aren’t currently relevant here. We are nowhere close to being Hawaii.

The proposed RCA regulations would allow net metering to gradually expand from tiny to small. This won’t be enough to produce more solar than we can use during summer days. On the other hand, distributed solar also won’t save us from turning on inefficient power plants at peak hours or allow us to build smaller powerlines. Our peak hours are in winter, and we don’t need to turn on other power plants to cover them.

Distributed solar probably saves more fuel than I’ve calculated here. There is line loss getting grid power to where it’s used, and power plants themselves use fuel. And all the saved fuel could be more expensive. I modeled the Cook Inlet gas conservation benefit based on $12/Mcf gas, but imports could cost much more, especially if we don’t get an import facility built soon enough.

In Conclusion

There is no ‘right’ or ‘fair’ answer on distributed solar policy or electric rate structures in general. All we can do is look at the potential impacts of any policy change. From where we’re at on the Railbelt today, allowing net metering to grow is a no regret move that could have a small benefit on overall fuel burning and the Cook Inlet gas crisis.

The proposed RCA rule changes to increase the net metering ‘cap’ to 20% of demand (around 2% of energy) simply requires the utilities to allow solar systems to continue to connect in the future as they have in the past, up to a level where they will remain irrelevant to other consumers. By itself, that doesn’t do much.

I’ve already shown that rate impacts to other customers would be tiny if we had that much net metering. Additionally, of all the Railbelt utilities, only the smallest (HEA) is close to its current cap, and no utility has ever actually cut off connections when the cap is reached (MEA spent years allowing connections above the cap before raising it). So the cap has had no impact whatsoever on net metering buildout so far. Changing the cap does nothing to change the incentives, which aren’t all that great for many consumers. It also doesn’t change the barrier of high up-front costs.

Policies that change net metering incentives could do a lot more. Annual net metering would allow people to get retail-rate credits for extra power they produce in summer that currently only gets wholesale rate credits, likely driving more installations. On the other hand, a change to ‘net billing’ would get rid of retail-rate credits entirely and give people only wholesale credits, likely shutting down the industry.

Community solar policy is more complicated, and deserves its own post. It’s more accessible to consumers than net metering, and while the impacts I’ve modeled here (as if it was equivalent to net metering) are a reasonable placeholder, implementation will matter a lot. It could end up being a better deal for consumers than net metering, or worse, and we also need to consider the incentives for the solar developers.

Anything that addresses distributed solar specifically is limited in its utility-scale impact, because it targets such a small portion of our grid. There are other ways to change rates that would have more dramatic impacts. Sometimes, utilities charge higher per KWh rates once consumption gets beyond a certain level. Renewable Energy Alaska Project proposed this as a gas-saving conservation measure in the Chugach rate case. Power Cost Equalization does this as well, with a cutoff on eligible kilowatt hours in a month. This incentivizes conservation, but disincentivizes electric cars and heat pumps, which also save fuel and energy. Other utilities do exactly the opposite, charging lower per KWh rates at higher use levels. MEA does this. This could make electric cars and heat pumps more attractive, but disincentivizes conservation.

You can comment on the RCA regulations until November 12.

Sources, assumptions, and methods

All utility level data from RCA filings and the EIA

Actual household bills are based on the most recent full year available, and are a very non-random sample of people who shared them with me, all served by HEA.

Rate impacts from solar systems were calculated separately for each utility, and weighted averages used for the Railbelt-wide number.

Net metering systems were modeled by taking average monthly use for a residential consumer for each utility, and combining that with monthly home solar capacity factors based on actual data for HEA and CEA systems, and combined with PV watts estimates to extrapolate to MEA and GVEA territories.

For Railbelt-wide rate impacts, I assumed all net metering (and all community solar) was made up of 6KW systems (the average size) installed on an average use home. Electric bills for these houses were calculated based on Q3 2024 rates for each utility. Real net net metering systems are probably more often installed on homes with above average use.

To determine the rate impact, I subtracted COPA payments from the annual bill, to determine the net metering customer’s contribution to fixed costs. The difference between this number and the average household’s fixed cost contribution was considered to be a revenue loss to the utility. For gas-dependent utilities (all except GVEA), I assumed that each KWh of solar power acted to ‘save’ cheap Cook Inlet gas for future use, and that the cost difference between producing a KWh at a utility’s current gas costs and at $12/Mcf is a revenue benefit to the utility. Rate impacts were determined by applying these revenue impacts on a per KWh basis to the utility’s entire retail sales.

I did not model reduced losses from distributed generation, but Railbelt utilities generally report losses of around 4.5-6%.