We’re making an Integrated Resource Plan for the Railbelt. Let’s not repeat our mistakes.

In 2020 the legislature passed a bill which created a new group to coordinate the Railbelt. This particular acronym-rich entity is an Electric Reliability Organization (ERO) named the Railbelt Reliability Council (RRC). Unlike past groups, this one includes both the utilities and a variety of other stakeholders. It’s been tasked with making reliability standards (which it has been quietly doing for some time) and creating an Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) for the Railbelt, which it’s working on at a rapid pace right now.

An IRP is a roadmap for the electric grid. It’s supposed to model various scenarios and then choose a set of stuff -- power plants, power lines, batteries, efficiency programs, load management programs -- which will be the option with the ‘greatest value’ for the next 20 years, updating every two years along the way.

There have been various Railbelt-wide planning processes over the years, none of which actually got implemented. The post-mortem on these has largely been about the framework -- whether and how the different utilities worked together. For more on that, Phil Wight has an excellent article about the entirety of Railbelt grid history.

Leaving that aside for the moment, what about the plans themselves? What did those 2008-2015 planning documents say about the future we’re living in now in 2026? What did they get right or wrong in their assumptions? Would we be better off if we had followed them?

I’ve been involved in one of the working groups for this new version of the IRP (filling the “small consumer” stakeholder role for AKPIRG in the objectives working group), and I like homework, so I tried to figure it out.

The plans built more stuff than we actually did, for a load bigger than we actually have - the result in 2026 would have been a power cost higher than we pay today. Those costs were front loaded and expected to decrease into the future, but to remain above 2010 costs. In contrast, inflation-adjusted bills have risen around 8% for the average household. The plan depended heavily on large hydro and geothermal projects later determined to be infeasible. It assumed we’d have a gas line already, and that gas would be both more expensive and more available.

In 2010, we proposed big, expensive, infeasible projects.

I dug up the tables and graphs from the 2010 Railbelt Integrated Resource Plan and did my best to compare the first chunk of that plan (which went to 2060) to what actually happened from 2011-2024.

2010 IRP capital costs from Appendix E. Actual capital costs approximated based on public announcements for each project.

The 2010 plan had us building nearly $5 billion dollars of power plants in the last 15 years. If that sounds like a lot to you, it sounded like a lot to the modelers as well. The financial analysis section (appendix B), admits there is no possible way for the utilities to fund the plan, and suggests that the proposed all-Railbelt organization that was under consideration at the time (GRETC) would sell $5.9 billion in bonds, which could be reduced somewhat if the state chipped in a $2.4 billion loan. This would have added around 7 cents per kilowatt hour in capital costs to rates.

That plan was anchored by several large projects that were soon declared infeasible. Nine months after it came out, the state abandoned work on the Chackachamna hydro project -- the largest project in the plan -- in favor of the Susitna hydro project, citing worse environmental impacts for Chackachamna, more complex construction, and the need to save more water for fish, which would reduce energy production. Susitna never happened either. In 2014, the geothermal company Ormat abandoned its exploration on Mt. Spurr, determining that it wasn’t commercially feasible. The third largest project; Glacier Fork hydro, was never more than a preliminary permit application. It would have been nearly the size of Bradley Lake hydro.

We knew, at the time, that these were all very uncertain: “Mt. Spurr, Glacier Fork, Chakachamna and Susitna should be pursued further to the point that the uncertainties regarding the environmental, geotechnical and capital cost issues become adequately resolved to determine if any of these projects could actually be built.”

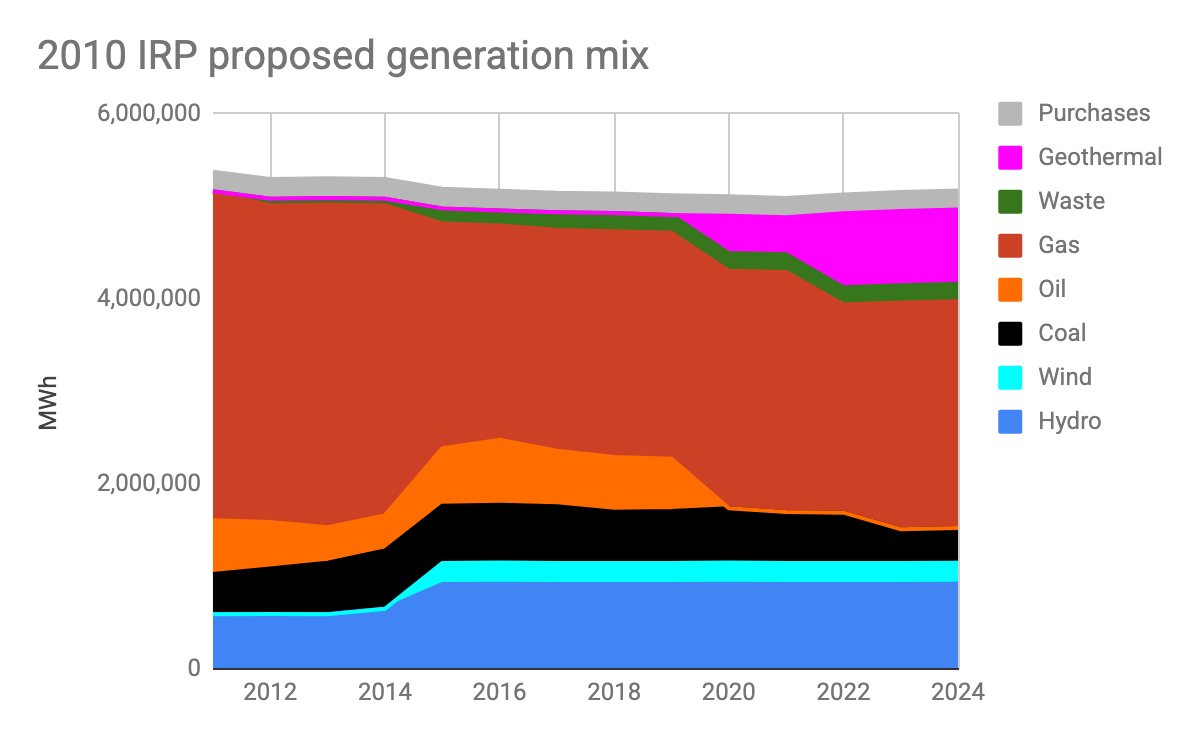

Even if the plan had happened, the largest hydro wasn’t scheduled to come online until 2025. Instead, we’d have spent the last 15 years shutting down oil power in the north (taking advantage of that 2018 in-state gas line!), and replacing some of the gas and coal with hydro, wind, and municipal solid waste, as well as “purchases” which I suspect is intended to include the Fire Island wind project.

Instead we doubled down on Cook Inlet gas

Gas plants were the one thing we spent more on than the 2010 plan suggested. They cost over a billion in total, but were small enough to be financed by individual utilities. Each gas-dependent utility bought or upgraded its own.

Did we build too much gas infrastructure?

The 2010 IRP worried we would. They thought the utilities’ go-it-alone approach would cost 5.6% more than the IRP plan. Afterwards Chugach’s 2015 analysis argued that this lack of coordination led to the Railbelt building $200-$500 million more in gas plants than was needed.

It’s kind of hard to untangle this -- can we simultaneously have spent billions of dollars less than we planned and hundreds of millions more than we should have?

All the new gas infrastructure made gas power more efficient than envisioned in the 2010 plan. If we’d produced the same amount of power with the older plants, we would have spent somewhere around $450 million more on gas (using Cook Inlet average prices rather than evaluating utilities’ actual fuel costs, and excluding post-upgrade savings attributed to utility consolidation and power pooling). But those savings are still only a little over a third of what those plants cost.

Some of those new plants are barely used

Could we have saved as much fuel with less expense? We have five gas plants that were built or upgraded in that time frame. In 2024, they had an overall capacity factor of 58%, which is a measurement of how heavily they were used (a plant producing maximum power every single hour of the year would have a capacity factor of 100%). The most used plant had a capacity factor of 82%, which is about as much as you can get in the real world (due to maintenance, etc…). But the least used plant, Soldotna, had a capacity factor of just 10%. It seems likely that we could have built less.

(for these calculations I’m not including the “duct burner” capacity of those plants that have it, because duct burners are an inefficient way to increase output, and wouldn’t be used unless they were needed)

We built efficiency rather than diversification

Gas use in reality was nearly exactly the same as it would have been under the plan. Where the plan anticipated load growth and new power sources, we got more efficient gas generation and a shrinking load.

The gas crisis ramped up more slowly than we thought. So we put off solving it.

The projected fuel trajectory at the time is surprisingly similar to what is being talked about today, where a few years of Cook Inlet gas were going to give way to imports (in 2013) and then an in-state gas line (in 2018), both of which would be substantially more expensive.

Although we didn’t build the infrastructure to get any outside gas supply, we spent quite a bit of money propping up the Cook Inlet gas system, through the CINGSA storage facility and the Cook Inlet oil and gas tax credits, which were mostly paid out as cash to Cook Inlet oil and gas companies. As a result, overall fuel-related spending was similar to the plan’s prediction.

Gas storage and tax credit amounts are 47% of total spend to adjust for the electric utilities’ proportion of Cook Inlet gas consumption

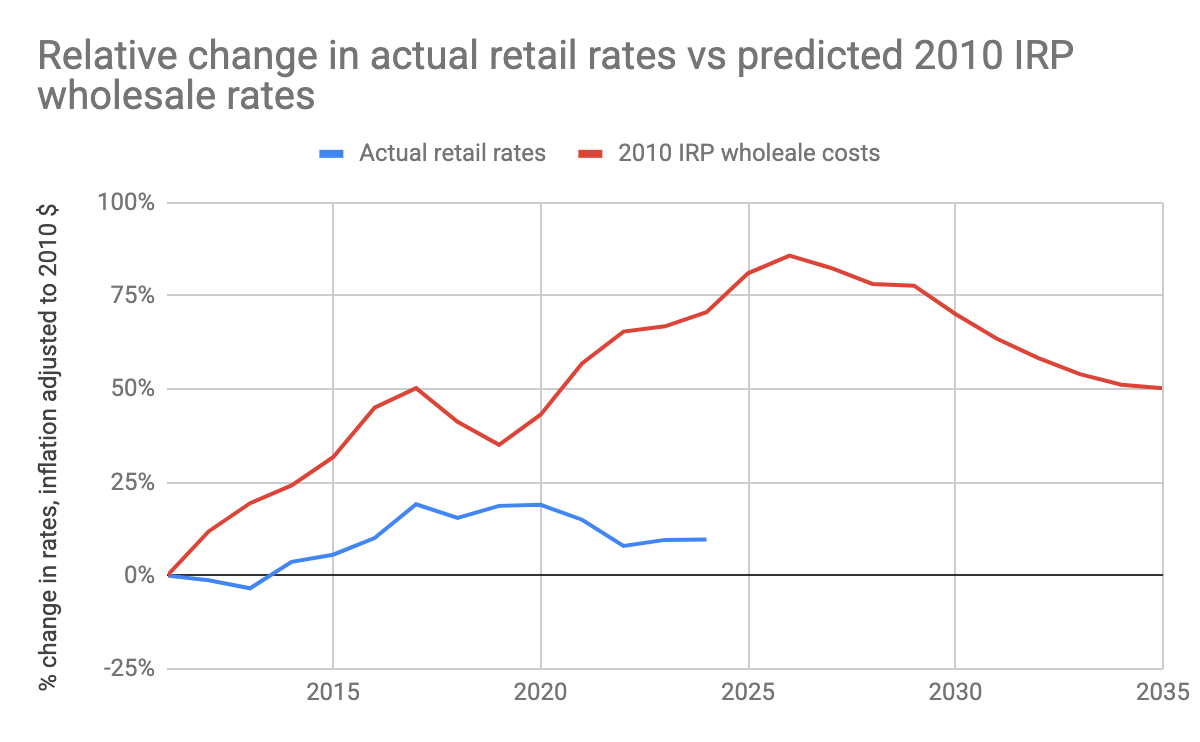

Costs were slated to rise much more than they did

It’s not possible to back out exactly what “wholesale power costs” are today on the Railbelt in the exact way they were looking at them. But average retail rates have risen only 10%, suggesting that wholesale rates probably haven’t jumped 75%.

We got lucky on efficiency

The 2010 IRP said that between 2011 and 2024, the utilities would spend over $100 million on energy efficiency programs for their members, categorized as “demand side management” programs. In fact, this was the one case where they didn’t choose the lowest cost plan that their model spit out -- they thought it would be even better to spend twice as much.

The state did spend over $600 million on energy efficiency in that time frame, through the Home Energy Rebate Program and the Weatherization Program, but those recommended measures primarily targeted heating fuel reductions. And while electric utilities didn’t spend money on electric efficiency, consumers did, reducing their use dramatically. This is why, although residential rates increased 15% over that time frame (inflation adjusted), residential bills only rose around 8%.

It was a bad plan. And the framework wasn’t set up to help anyone make good choices.

The plan made a lot of wrong assumptions. Some of them were egregiously wrong -- like the idea that every large barely-sketched-out energy project would be feasible, and that we could pay for them all. Some of them were more understandably wrong, like forecasts that predicted load would grow rather than shrink, that gas prices would rise more quickly, and that we’d figure out some other source of gas beyond Cook Inlet. Predicting the future is hard, but ideally, you’d have thought through your assumptions and sensitivities well enough that the edges of your ranges would at least end up overlapping with reality.

But really bad assumptions isn’t what I’m most worried about in the current IRP framework. Another big problem is that the framework wasn’t actually set up to help us choose between plans -- and making more reasonable assumptions won’t fix that on its own.

I’ve been critiquing this old plan based on the “1a/1b” scenario highlighted throughout most of the document. They actually had two other scenarios and 17 different sensitivities they modeled for the first scenario.

However, the two other scenarios are irrelevant, because they are scenarios for a dramatic increase in load that never happened. And while the sensitivities help illustrate some risks, they don’t suggest alternatives.

One set of sensitivities varies the assumptions, but keeps the plan constant. For example, if gas prices and capital costs go up, the suggested plan costs more. If there are tax credits for renewable energy, it costs less. Basically, this tells us “if costs change, prices change.”

The other set of sensitivities varies the plan, but keeps the assumptions constant. For example, six of the 17 sensitivities replace Chackachamna hydro with a different version of the Susitna project. They all show Susitna is more expensive. Which is obvious, because the way they got the first plan is by feeding it the default assumptions and asking the model to minimize costs. By definition, anything the model didn’t choose the first time is more expensive under that set of assumptions. This also doesn’t help anyone make decisions.

The only way to make choices based on sensitivities would be to vary both aspects at once -- assumptions and plans. One possibility is to allow the model to choose a new plan based on each different set of assumptions. I.e. “If gas costs are high, does a different plan make more sense?” This seems attractive on its face, and I think it’s what’s being proposed in the current planning process.

That won’t help either. The flaw here is that if you optimize for total cost across a set of different imagined futures, you turn the whole exercise into a contest of “which predictions are most believable?” And you’ll choose the same default assumptions -- after all, those were already the modelers’ best guess.

All of this would just spit out the same bad plan.

We need to model the future to make choices, but we need to do it in a way that recognizes that some of our assumptions are inevitably wrong -- and allows us to make choices that are robust across a wide set of assumptions and also across a varied set of values. That includes wholesale power cost, but also all the other pieces that make up “greatest value,” including stability, resilience and environmental impacts.

What now?

What I’m hoping for this time is something that helps us make good choices in a world that’s even more uncertain than it was in 2010.

We need to vary plans and assumptions independently, so we can compare multiple different plans across the same set of possible futures. To do that, we need some meaningfully different plans to start out with. What if we had made one plan that minimized overall costs, one that minimized emissions, one that minimized up-front capital costs, one that minimized cost volatility, one that focused on lots of small projects, one that focused on a diversity of resources, etc…? We also need an assumption space that is broad enough to encompass most possible futures, across all the relevant dimensions.

Maybe we’ll find plan A is cheapest under a certain future scenario, but super sensitive to changes in those assumptions, while plan B doesn’t look the best in any one of them, but is pretty good across the widest range. We’ll only know that if we set up the model to tell us.

I hope we will.

There’s been a lot of good discussion about what matters to different stakeholders, but not enough clarity, at least from my perspective, if what gets spit out at the end of this all will really let us evaluate those values.

The next public meeting is Tuesday February 17 at 1PM. The public can make comments at the beginning or end or submit them in writing. The draft working objectives document is here.