How much Cook Inlet gas can we conserve?

Known near-term renewable projects and heating efficiency can make a substantial difference. Not enough to avoid imports entirely, but enough to give us time to set them up.

There are more than ten separate energy-related bills in the Alaska legislature right now, largely catalyzed by a flurry of concern over the impending shortfall of Cook Inlet gas. At a February hearing, Enstar’s president said that he was worried about running out of gas before imports could arrive around 2030. Most of the bills, however, set up long term subsidies for gas with little potential impact in the near-term. We may not be able to build an import facility before 2030, but we can’t build much of anything else before then either, other than projects that are already close to ready to go. Luckily, there are a number of renewable energy projects in that category.

The increased price of imported LNG is not, in itself, a crisis (more on that in a later post). Actually running out of gas -- being unable to provide enough heat and electricity to the Railbelt without other options in place -- would be a crisis.

So we decided to analyze what we see as one of the biggest missing pieces of the conversation.

How much, and how fast, can we reduce consumption?

Consumption hasn’t been flat in the past: Historically, every official report on Cook Inlet gas shows future consumption flat, and every report has been wrong. In 2011 the state predicted 90 BCF of use every year, by 2018 it was 80 BCF, and in the 2022 report report, it was 70 BCF. Much of that was due to more efficient gas-fired power plants. There’s little opportunity left to improve our gas plants, but a lot of opportunity to use them less.

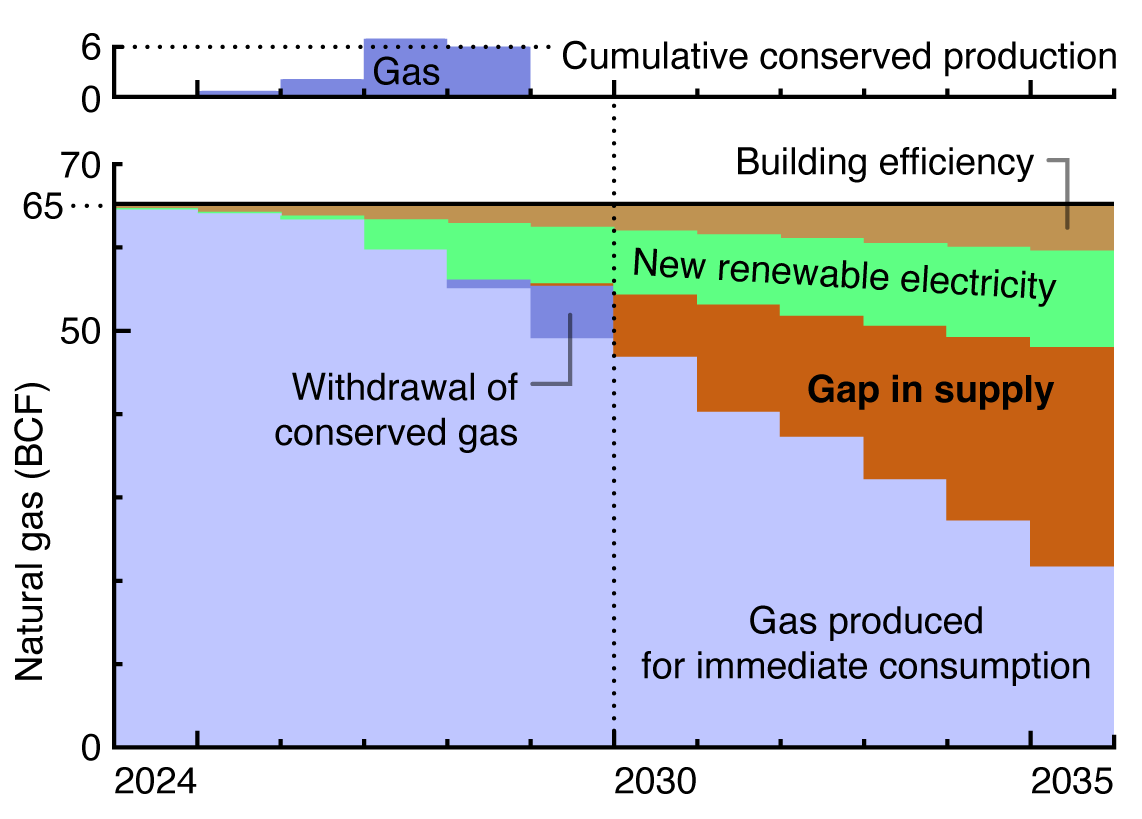

Consumption doesn’t have to be flat in the future: Using numbers from the utility working group 2023 report, we modeled known near-term renewable projects and an increase in home efficiency. With those straightforward measures, we can reduce gas use below the production estimates for several years. These gas savings (in the form of stored gas or unproduced gas) can be used to offset production declines in later years.

The utility analysis shows a gas supply “gap” of 8 BCF in 2028. In our analysis, this gap is pushed back by nearly two years.

Utility demand of 65 BCF from the mid-case of the 2023 working group report (p 12-14), production data from DNR’s truncated 2022 forecast.

How did we come up with that?

Current demand can be broken into three main categories; industrial use, heating, and electricity generation.

Industrial: Most of the industrial use is oil and gas field operations. Those have remained relatively constant, even as production has dropped dramatically (slide 10 - from DNR), and may be a sort of unavoidable ‘parasitic load’ on the system. Other industrial users include the Tesoro refinery. We didn’t model any decrease in industrial use.

Heat: Efficiency measures are effective. Overall, Enstar’s residential customers use 10.5% less gas today (weather normalized) than they did in 2007, before the Home Energy Rebate and Weatherization programs. Participants in the Home Energy Rebate program reduced their gas consumption by 26%. Those programs reached fewer than 20% of Enstar’s customers, suggesting there are significant savings still possible.

However, heat consumption has to be reduced at the level of each individual building, through weatherization, furnace and appliance upgrades, behavioral changes, or switching to a different heating source. That makes it hard to do quickly. The number of inefficient heating systems and homes is smaller now than in 2007. Additionally, the economics still favor switching to natural gas for homes heating with oil or propane (as I showed in this post).

Putting all of this together, we decided to model a 15% total decrease in gas for building heat, ramped in over 10 years. That will likely require incentives, but not necessarily from the state. IRA funds will provide rebates up to $8000 per home for efficiency upgrades, tiered based on energy savings and income.

Electricity: This is the easiest sector to reduce quickly, displacing a portion of gas-powered electricity with renewable electricity. There are a number of nearly shovel-ready wind and solar projects being pursued on the Railbelt today. Over the longer term, NREL’s recently released report shows that a 76% renewable system is the cheapest way to power the Railbelt, substantially cheaper than keeping our current generation mix.

Between now and 2030, we modeled only those renewable projects currently in advanced stages of negotiation with utilities or planning by utilities, using their most recently-reported completion dates from news articles or utility filings and reports. Houston solar (already operational), Kenai solar and landfill gas (2026), Shovel Creek wind (2027), Little Mount Susitna wind (2027-8), and Great Lands solar (2028 - Chugach electric personal communication). Home net metering was assumed to increase at the same rate as recent years, around 2.5MW per year. Annual generation assumptions can be found in this post. Shovel Creek wind was presumed to primarily displace oil generation, while all other renewables were assumed to displace gas, at the current Railbelt efficiency adjusted for part-load and operating reserve fuel use impacts.

Beyond 2030, we ramped renewable energy linearly to the 55% by 2035 renewable target set in the proposed RPS bill.

Previously stored gas can fill the remaining gap: Our analysis shows a supply gap of 0.3 BCF in 2029, and 7.5 BCF in 2030, potentially before imports could arrive. However, Cook Inlet has a small ‘savings account’ of sorts in the form of stored gas, which has been accumulated over the past couple decades, largely by Hilcorp (slide 6). The current amount stored is equal to about half a year of current demand.

Without the savings we modeled, the cumulative supply gap would be 43 BCF by 2030, more than is in storage. With them, our cumulative cap could be filled by less than a quarter of the currently stored gas.

What about subsidizing gas? Last time we tried, we spent around $1.5 billion dollars in cash to Cook Inlet producers. In some years, those subsidies were more than the entire cost of gas for Enstar and all the electric utilities put together. A decade later, we find ourselves in the same place.

So should we spend $10.7 billion instead? The Alaska Gasline Development Corporation has been pushing their North Slope pipeline for years, with no luck so far getting the investment needed to pay for it. Now they are back to promoting a “phase 1” in-state pipeline for $10.7 billion dollars, which could theoretically, if we start now, beat LNG by a few months. And while they hope it will be an export project eventually, that hasn’t panned out so far. “In-state” means that one way or another, Alaskans are paying for it.

Alternately, $10.7 billion could pay all gas and electric bills for all Railbelt households for 18 years.

Or give every household in Alaska over $40,000 for weatherization and efficiency.

Or build enough wind and solar farms to produce more than twice as much power as the Railbelt currently uses.

HB 222 directs the state to actually invest the permanent fund in a gas pipeline

What about royalty relief? There are two proposals to cut royalties on new gas (HB 276 and 223), and one to give tax credits for jack up rigs drilling in the inlet. These aren’t refundable, so they are less egregious than the cash credit subsidies of the past, and far less so than subsidizing a gas pipeline. But they’re unlikely to lead to more gas production in the short term, nor to stop the need for imports in the medium term, so they don’t address the main problem.

Exploration will be as expensive, risky and time-consuming as it ever was. Royalty relief only kicks in once gas is already being produced from these new areas, so will probably come after 2030, if at all.

It could allow someone to sell gas that otherwise would be too expensive for the market to bear. We already have lots of unused flexibility in prices. Cook Inlet buyers, worried about the costs and availability of imports, would likely sign contracts for new gas at prices much higher than today. But those contracts aren’t being offered. Price does not appear to to be a limiting factor in current investment.

In Conclusion: Don’t panic, build an import facility, move forward with renewable projects already in the pipeline, and make our homes and businesses more efficient. Over the longer term, gas consumption can continue to ramp down. And if we avoid locking ourselves into long term contracts or expensive subsidized fossil fuel infrastructure, imports will allow us the flexibility and time to develop local renewable energy for both electricity and heat.